MachA, VaronA, MasculinA : la femme artiste dans la barbe de l’art cubain

Participants

OPENING + PERFORMANCES

Thursday, June 5th, 6:30PM

Free Entrance

EXHIBITION – June 5th to 20th, 2014

Tuesday to Friday from 10am to 5pm

@ STUDIO XX – 4001, Berri (corner Duluth) space 201

Curators :

Analays Alvarez Hernandez

Laura Verdecia Blanco

Julio César Llópiz

Studio XX is pleased to present the international exhibition MachA, VaronA, MasculinA : la femme artiste dans la barbe de l’art cubain, which will be held from June 5th to 20th in the gallery space of Studio XX. Curators Analays Alvarez Hernandez (Montreal, Canada), Laura Verdecia Blanco (Miami, USA) and Julio César Llopiz (Havana, Cuba) are pleased to collaborate with Studio XX in presenting the North American premiere of this group exhibition which brings together the work of five Cuban artists. On opening night, performances by Julio Cesar Llopiz, Grethell Rasua and Naivy Perez will be featured. A presentation by the artists and curators will be held at the Femmes Br@nchées # 102 on June 19 and in parallel, a performance event in collaboration with Encuentro will conclude the project on June 24th at the Phi Center.

MachA, VaronA, MasculinA : la femme artiste dans la barbe de l’art cubain

The popular expression Macho, varón, masculino! (Male, boy, masculine !) – pardon the redundancy – testifies to the place occupied in Cuba by the social construction of virility. As a means to strengthen and affirm male identity, this typically Cuban expression foregrounds an interdependence between virility and heterosexuality, and on virility and domination. In order to give a title and tone to this project that focuses on the Cuban woman artist in a largely male-dominated society, we have intentionally feminized the expression in question.

If the socio-political changes realised by the Cuban Revolution throughout the 1960s gradually provided major advances for women’s rights in general, it took much longer for women artists to break into the Cuban art world. It wasn’t until the 1980s, as part of a broader revival of national culture, that there was a significant turning point in the interrogation of issues concerning women artists, by women artists (Marta María Pérez Bravo, Ana Albertina Delgado, María Magdalena Campos, Consuelo Castañeda , Rocío García, etc).

Cultural institutions followed this « feminist blast-off » as best they could. At the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana (MNBA), pantheon of Cuban art, artists such as Juana Borrero (1877-1896), Amelia Peláez (1896-1968), Antonia Eiriz (1929-1995), Zaida del Río (1954) or Belkis Ayón (1967-1999) found a place but the works of these artists seemed like tiny sparks in a landscape where the male voice was so dominant.

In light of this context dominated by a largely patriarchal vision of historiography, the exhibition MachA, VaronA, MasculinA is intended as a platform for experimentation with the aim to explore the role of women artists in the history of the Cuban art in the collection of the MNBA . Five young Cuban artists (three women and two men), whose work is recognized both internationally and and locally context, execute this critical exercise. We are as interested in the perspective of male artists on the women’s artistic practice as we are by a female perspective. With the use of classic and new mediums (performance, video, installation, participatory action, engraving, etc), Naivy Pérez, Grethell Rasúa, Adislén Reyes, Levi Orta and Julio César Llopiz reinterpret (and reappropriate) iconic works, recurrent themes and pictorial references associated with the creative world of the woman artist.

The live streaming performance by Naivy Pérez, A drop of honey, depicts a scene where the artist submits to the “agony of the water drop” a Chinese torture method. She replaces water with honey, a substance with medicinal properties. In the “torture chamber”, a form of abandoned place, the only audible sound is the drop of honey hitting Pérez’s head every second. This piece is a nod to the powerful performance work of Ana Mendieta and Tania Bruguera, two internationally recognized Cuban artists. Like Mendieta and Bruguera, Pérez uses metaphors for power, martyrdom and survival, but her approach is characterized by a playful tone. A drop of honey also explores the impact of new technology on our lifestyles and behaviour, including the logistics used in crimes such as kidnapping and torture. The telephone, for example, was once the preferred tool for for kidnappers to request ransom. Today, audio/video software like Skype replaces this traditional method and adds the dimension of an image, in this case « making » the viewer attend a live torture scene, and providing a front and centre point of view, which engages the viewer even more in this (false) story.

Also in the world of video performance, Grethell Rasúa interprets the cliché Cuanto encontró para vencer (1) (2000) from the Cuban photographer Marta Maria Pérez Bravo. Pérez Bravo connects the symbolism of Afro-Cuban religions with purely artistic components while standing in front of a camera and staging highly spiritual settings. Standing in front of a black wall, Rasúa, bare-chested, back to the audience, wearing a skirt and a white turban, holds four candles on her outstretched arms. A video showing a hand carving words on a rock scrolls on the back of the artist (and gives the effect that the carving is done on Rasúa’s back). This performance illustrates the concept of resistance: facing adversity, we do not fail, but rather believe in ourselves and fight so that our desires and interior shine a light on the the road ahead. The contrast between light and darkness expresses the (magic) cohabitation between the religious and artistic worlds in the roots of Cuban society.

In a more traditional vein Adislén Reyes presents Explosión Roja, a set of twelve artists’ books (limited edition). The number of prints corresponds to the number of months in a year. Reyes wants to establish the analogy between the intervals of the menstrual cycle and the process of publishing engravings (1/12 , 4/12, etc). Subject to a variety of prejudices in the popular imagination, at times a source of contempt and superstition, or a symbol of impurity and inferiority, this monthly blood flow is nevertheless the condition of that makes it possible for human beings to reproduce. Engraving, known for giving birth to aesthetically impeccable works aesthetizes this biological phenomenon. Reyes’ “red explosions” further explore the relationship of women artists in an artistic discipline that continually reinvents itself and is carving out a new place in the practice of the young generation of artists. Despite the fact that throughout the history of Cuban art, women have repeatedly attempted to infiltrate the world of engraving, only a select group managed to cross the threshold into the pantheon of art in Cuba (2).

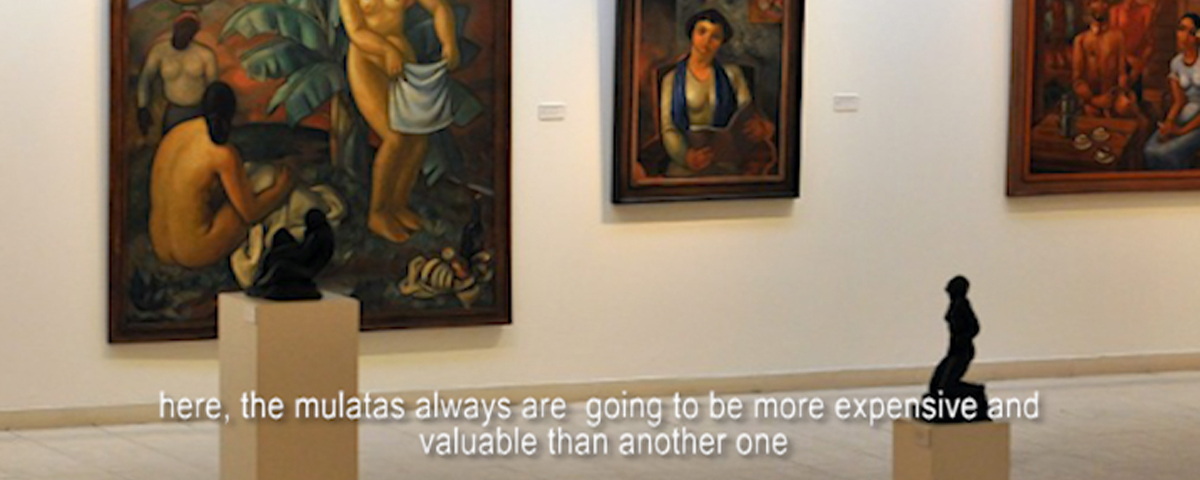

Levi Orta focuses on the representation of the female figure by male artists, and thereby the image of women as a stereotype of pleasure. Simultaneously, he wants to make a link to the old art-prostitution relationship. In Olympia con nota a pie de página, a sex industry professional walks the halls of the MNBA. She offers her services to potential clients as a tour guide-interpreter. The selected pieces for “interpretation” are those that address the woman as an object of pleasure. Orta confronts the fetishs of woman as a both pleasure and intellectual agent, all at once.

The co-curator of this exhibition, Julio César Llópiz concludes the artistic contributions with his piece Poster redesigning exercise (after Asela Pérez). Llopiz takes, as his starting point, a graphic work created in 1970 by the illustratore, Asela Pérez. This poster, now famous in Cuba, is the silhouette of South America in the form of a hand grabbing a gun. Poster redesigning exercise (after Asela Pérez), a work straddling graphic arts and participatory action, explores the confinement of women to certain interests but not to others, at the same time as triggering a reflection on both the handling of firearms and on the “hand” that distributes them.

Analays Alvarez Hernandez

Montreal, May 8, 2014

Notes

(1) Ce qu’il lui a fallu affronter pour vaincre (notre traduction).

(2) Nous pensons notamment à Lesbia Vent Dumois (Carrera de bicicletas, xylographie, 1961), à Belkis Ayón (La cena, collagraphie, 1988) et à Sandra Ramos (La maldita circunstancia del agua por todas partes, chalcographie, 1993).